Perceptions of Sandtray as a Component of a Mindful Self-Compassion Workshop to Reduce Burnout in Nursing Students

V. Fawn Colburn

HCA Healthcare Corpus Christi Medical Center – Bayview, Corpus Christi, Texas, USA

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-7601-5999

Claudia Guerrazzi-Young

Jack C. Massey College of Business, Belmont University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8020-1202

Danielle J. Durant

College of Nursing and Health Sciences, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, Texas, USA

Behavioral Health and Health Policy Practice, Westat Inc., Rockville, Maryland, USA

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4282-6797

https://doi.org/10.58997/wjstp.v1i12.59

There are no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to V. Fawn Colburn, HCA Healthcare Corpus Christi Medical Center – Bayview; 6629 Wooldridge Road; Corpus Christi, Texas 78414. P: 361.986.8276; E: Vanessa.Colburn@hcahealthcare.com

Abstract

Burnout is an increasing phenomenon in healthcare resulting in many nurses choosing to leave the profession, creating shortages. Nursing students experience burnout the same way professional nurses do; however, equipping them with tools to build strength and resiliency may offer protection against burnout in the future. Mindfulness-based practices, like mindful self-compassion, have demonstrated effectiveness at reducing burnout in healthcare workers. Mindful self-compassion has three components: moments of (1) self-kindness, (2) shared human experience and (3) mindfulness. We, the authors, developed a workshop intervention based on principles of mindful self-compassion to teach undergraduate nursing students tools for managing emotional stress and reducing feelings of burnout. The use of sandtray was an essential component of this training. Three sandtray builds incorporated into the workshop served as the primary mechanism for fostering the shared humanity component required for mindful self-compassion. Qualitative feedback regarding the sandtray component was gathered immediately following the workshop and analyzed for common themes. The response to the experience was overwhelmingly positive. The feedback word cloud reporting – helped, think, reflect, visualize, express, open, and learn, as some of the most used phrases to describe the experience, as well as liked, loved, and great. Additionally, participants were asked what the most impactful experience was they took away from the workshop; the feedback word cloud indicated the sandtray component, specifically the "Strength Tray," as the most impactful. Using sandtray as a mechanism for fostering moments of shared humanity as part of a mindful self-compassion workshop is a novel application of this therapeutic technique and proved a valued and celebrated aspect by the participant population, undergraduate nursing students.

Keywords: sandtray, nursing, burnout, mindfulness, sand therapy research

The United States is in the midst of a critical nursing shortage that is expected to continue through 2030, and a primary issue driving this shortage is nurse burnout (Haddad et al., 2023). A recent study published in JAMA indicated among nurses who reported leaving their jobs in 2017, 31.5% reported burnout as a reason (Shah et al., 2021). Burnout can be defined as "a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment, which can occur among individuals who work with other people in some capacity" (Maslach, 1993, p. 20). Equipping nursing students with tools for managing the drivers of burnout – a high-demand work environment (Dall'Ora et al., 2020) and empathy fatigue (the emotional and physical exhaustion that can happen as a result of caring for others on a daily basis) (Miller et al., 1988) – could address nurse burnout early, possibly leading to reduced nurse turnover and higher quality patient care.

A systematic review conducted in 2020 concluded that mindfulness-based stress reduction – techniques focused primarily on mindfulness meditation and yoga – is an effective intervention that can help improve the psychological functioning of healthcare professionals (Kriakous et al., 2021). Another systematic review in 2019 found that mindfulness-based interventions – a more generalized set of interventions with mindfulness at the center – were proven effective at improving the mental well-being of physicians, especially when employed in a group-based training format (Scheepers et al., 2020). Similarly, in 2021, a systematic review and meta-analysis specifically investigated the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout in primary healthcare professionals. They found these to be effective and recommended their implementation for reducing burnout in this population (Salvado et al., 2021). Further, in 2018, a randomized controlled trial found that mindful self-compassion training reduced stress and symptoms of burnout among practicing psychologists; specifically, the training "appeared effective to increase self-compassion/reduce self-coldness [associated with burnout], and to alleviate stress and symptoms of burnout" (Eriksson et al., 2018, p.1).

Specifically aimed at empathy fatigue, mindful self-compassion combines the skills of mindfulness and self-compassion to enhance a person's capacity for emotional wellbeing, encouraging emotional resilience. It requires three elements: (1) self-kindness, (2) recognizing common humanity, and (3) mindfulness (Neff, n.d.). We designed an intervention, an educational workshop, to teach mindful self-compassion practices to student nurses to lessen their feelings of burnout and improve their understanding of the concepts of mindfulness and self-compassion, with a novel approach. The workshop incorporated group sandtray exercises. This article focuses on the opportunity for sandtray to be used as a mechanism for operationalizing one of the elements of mindful self-compassion, recognizing our shared human experience; how sandtray was integrated into a broader mindful self-compassion intervention for undergraduate nursing students; and the perceptions of intervention participants on the use of sandtray for these purposes. We were interested in understanding how participants felt about the sandtray component of the workshop and how it impacted them.

Mindful Self-Compassion: An Opportunity for Sandtray

Pioneered by Drs. Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer, mindful self-compassion combines the tenets of mindfulness and self-compassion, creating a powerful tool for emotional resilience. Mindfulness is the practice of gently and intentionally turning our attention to the present moment, away from ruminating about the past or worrying about the future (Neff & Germer, n.d.). Self-compassion refers to relating to ourselves in instances of perceived failure, inadequacy, or personal suffering, with compassion, which is warm, caring, and non-judgmental (Neff, n.d.). Combining these concepts, mindful self-compassion is becoming curiously aware of our difficult thoughts and emotions as they arise and responding to those with kindness, sympathy, and understanding (Neff & Germer, n.d.). It requires three elements: (1) kindness vs. self-judgment – rather than self-criticism in moments of failure or feelings of inadequacy, we are gentle and understanding; (2) common humanity vs. isolation – rather than feeling as if we are the only one to suffer, we recognize that suffering and feelings of inadequacy are part of the shared human experience, something we all go through together, and (3) mindfulness vs. over-identification – rather than suppressing, exaggerating, or getting so caught up in our negative feelings that we identify with them, we observe them with openness, non-judgment, and detachment, understanding we are not our feelings (Neff, n.d.).

The first and third elements of mindful self-compassion, treating ourselves with kindness in moments of perceived failure and inadequacy and observing difficult feelings with neutral curiosity in the moment, are both practices we can learn to do internally, at an individual level, without engagement with the outside world. However, the second element is different; it requires acknowledgment of others' experiences and suffering so we can place our own into perspective and understand we are not alone in our pain. By its nature, it necessitates some interaction with other people and is more difficult to operationalize in a workshop setting. This presents an opportunity for group exercises using sandtray, an effective tool for fostering meaningful self-exploration and expression, to be incorporated into a broader mindful self-compassion intervention to reduce feelings of isolation and create moments of shared humanity.

Intervention

Population

We developed an intervention based on mindful self-compassion principles to address burnout in undergraduate nursing students at Texas A&M University, Corpus Christi. These students completed their rotation in NURS-4564: Nursing Care of Psychiatric Clients at Corpus Christi Medical Center-Bayview Psychiatric Hospital in fall 2022. As part of their course curriculum, these students participated in one 4-hour workshop, with about 10 students each, led by a licensed therapist certified in sandtray; the clinical course instructor participated in the workshop and was not involved in the study. Eight workshops were offered, reaching approximately 80 students in total. The workshop was a required part of the course curriculum, but opting to join our study, providing pre- and post-feedback related to their feelings of burnout, understanding of mindfulness and self-compassion, and impressions from the experience, were optional. We had 69 students consent to participate in this IRB-approved study. The intervention was conceptualized by the workshop lead in partnership with one of the researchers who holds an advanced practice certificate in mind-body medicine; the agenda combined sandtray builds, lecture and training in mindfulness and self-compassion principles and techniques, and a discussion of trauma-informed care principles. The overall goal of the workshop was to see significant differences in participants' understanding of mindful self-compassion immediately following the session, as well as reduced markers of burnout 2 months post-intervention. However, this writing focuses on one subset of this larger study, the perceptions of the intervention participants on the use of sandtray as a tool for teaching mindful self-compassion (Figure 1).

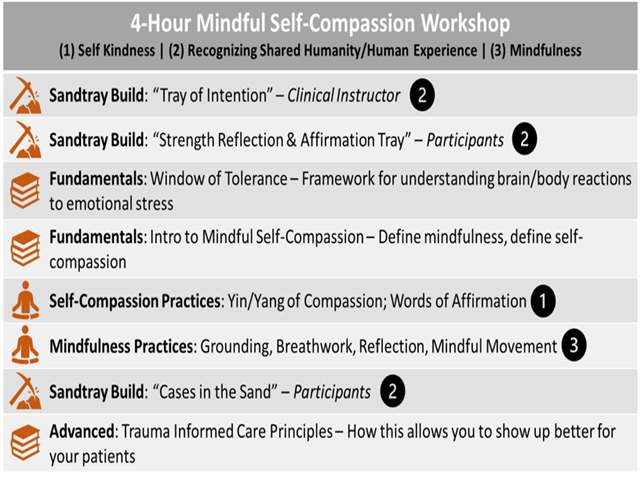

Figure 1: Four-Hour Mindful Self-Compassion Outline

Workshop

Figure 1 outlines the agenda for the 4-Hour Mindful Self-Compassion Workshop provided to undergraduate nursing students; the numbers after each activity refer to the component of mindful self-compassion, the task aimed at building.

Sandtray Build: "Tray of Intention." To introduce students to the concept and application of sandtray, each workshop began with the clinical course instructor building and presenting a "Tray of Intention." Instructors were directed by the workshop lead to building a scene that depicts their hopes for what students will get from the workshop, as a nursing student, and beyond. They also set an example of using sandtray to facilitate meaningful and honest expression. An example of an instructor's "Tray of Intention" has been provided in Figure 2. The instructor added imagery to share a little bit about herself; the coffin in the middle reminded her of the passing of time, as the instructor revealed this is her last semester before retiring and focusing on being a grandmother. The instructor placed the baby and dogs near the center of the tray, close to the coffin, mentioning these represented her two dogs, to whom she is close, and the newest grandbaby to be born in a few months. Behind the dogs and baby are images the instructor placed to indicate her heritage, as she identifies as part Mexican and part Native American. She shared with students her appreciation for heritage and her profound respect for the work ethic of her elders and deceased family members, which served as motivation and inspiration for her to become a "healer."

The instructor also added imagery for encouragement and inspiration; she spoke concretely about the importance of student nurses relying upon their teammates in the profession, as indicated by the baseball player figures. The "Peanuts Gang" depicted the students and the different personalities found in the nursing profession, as well as the sense of belonging and connection despite these differences; the Mexico hat atop one character was added to indicate culture. Near the "Gang" is a snake; the instructor warned students, "There are sometimes snakes in this profession; people who don't see the good in you or the patients, and you have to watch out for them." Finally, the signs with phrases indicated themes of school and teamwork, as she voiced encouragement to her students about continuing to work hard in school, completing their tasks, believing in themselves, and ultimately, graduating. She reminded students they are already teammates by being in a cohort together and to seek support from one another while going through their studies.

Sandtray Build: "Strength Reflection and Affirmation Tray." Following the instructor's build, the workshop progressed to the first build by individual participants, the "Strength Reflection and Affirmation Tray." For this build, participants were instructed to each build a scene that represented their various strengths; the goal of this activity was to have the participants begin turning their attention inward and identify and affirm the positive aspects of themselves, as well as build connection with one another and the bravery to share honestly, opening their mind and hearts to the teachings and practices that would follow. An example of a "Strength Reflection and Affirmation Tray" has been provided in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Nursing Instructor Tray of Intention (Used with permission)

The student added imagery to depict her strengths; she placed the card at the back of the tray, mentioning, "This card is about the infinite and the finite" and "It spoke to me because my aunt told me when I was eight years old that the dead teach the living." She shared that her aunt was in medical school at the time and went on to become a neurologist. The student said this is why she placed the "Grim Reaper" in the center of the tray, to honor the dead who continue to instruct her as she goes through her nursing program. The student added the laptop to represent the medical device she uses for managing her Type 1 Diabetes, which she believes has a positive impact on her life, "I am grateful for it;" this gratitude stems from being able to manage her own medical needs. She placed the dog and the pet food in the tray to indicate the importance of her family dog in her life, stating, "We've had a dog from this particular family line since before I was born;" this was her way to represent a connection to her family, who encourage her in her studies. The diploma was placed to represent graduation in the spring, and the debit card represents strength in managing her resources.

Figure 3: Participant "Strength Reflection and Affirmation Tray" (Used with permission)

Fundamentals: Window of Tolerance & Introduction to Mindful Self-Compassion. To provide participants with an awareness of how life events impact their emotional state, we introduced the concept of emotional regulation through the Window of Tolerance, a framework by Dr. Dan Siegel (1999). The idea here is we all have a window of optimal functioning where we feel present, calm, and safe. Where we are engaged and alert and can think and respond clearly. Ideally, we spend as much time as possible in this window. However, situations can and often do, pull us out of this window of tolerance into either a hyper-aroused state—fight or flight, emotionally reactive, hyper-vigilant, maybe even angry—or a hypo-aroused state—freeze, lethargic, numb, zoned out, shut down (Siegel, 1999). Our goal is to make our window of tolerance as robust as possible. We can handle increasingly difficult situations while remaining within it, become more aware of when we leave the optimal state, and take conscious, healthy actions to return to it. Mindful self-compassion was presented as the path to building a wide window of tolerance and returning to optimal functioning when emotions are pulled high or low; participants were provided with a definition of mindfulness and compassion and how the concepts come together to form mindful self-compassion.

Practicing Self-Compassion. Next, we discussed how to practice self-compassion, which first required understanding compassion comes in two forms, known as the yin and yang of compassion. This concept refers to the idea that compassion has two sides, depending on what is needed at the moment; it can be kind, gentle, validating, and soothing when aimed at stressful emotions, or fierce, powerful, protecting, and encouraging, when aimed at self-preservation, ensuring our needs are met, or motivating us to act or change (Neff, 2019). We paired this concept with words of affirmation, offering mantras to the participants to use in moments when either kind of self-compassion was required; for example, "I am doing the best I can," when gentle validation is required, and "I can do this; I am strong," when encouragement is required.

Mindfulness Practices. We provided training in basic mindfulness techniques aimed at helping participants come out of spiraling thoughts, negative self-talk, or overwhelming emotions and connect back to the present moment. The first technique we discussed was grounding, which can come in many forms: literal grounding, by stepping outside for a brief moment and touching the earth directly, and other grounding practices, such as color scanning, which requires locating a specific color in the environment for a few moments and tapping into our five senses, which requires taking a moment to identify one thing we can see, hear, taste, touch, and smell. We demonstrated breathing practices such as doorknob breathing, where we do a psychological sigh (Balban et al., 2023)—a deep inhale, followed by another sharp inhale, then released in a forceful exhale, a sigh—whenever we touch a doorknob or step into a new room, and stairwell breathing, where we step into a stairwell to do a few rounds of box breathing (inhale for a count of 4, hold for a count of 4, exhale for a count of 4, hold for a count of 4, repeat). Lastly, we provided a reflection technique, Rolfe's reflective practice, which is a framework for processing strong situational emotions quickly at the moment by asking ourselves three questions: what (What happened? Who was involved?), so what (What are the implications? What does this tell me/teach me?), and now what (What do I do next?) (Rolfe et al., 2010)?

Sandtray Build: "Cases in the Sand" Tray. Once the participants were equipped with tools for offering self-compassion, coming back to the present moment, processing strong emotions, and being comfortable with authentic sharing with one another, we moved into the final sandtray build of the workshop: "Cases in the Sand." This exercise asked participants to build a scene depicting a difficult medical case they had been involved with as a nursing student; the goal was to help process and clear their greatest vicarious trauma related to their new profession as a way to improve their resilience and demonstrate the importance of adequately processing difficult moments. An example of a "Cases in the Sand" tray has been provided in Figure 4.

The student added imagery to depict a recent medical case; she illustrated the story of a Guatemalan man who walked over 2,000 miles to get to Texas. The left side of the tray represents the challenges the patient experienced during his trek through the desert. As he had no access to food or water, he became ill and required medical care. The right side of the tray represents the struggle he faced to gain access to food, water, and basic medical care due to language barriers when first arriving at the hospital, which is when the student encountered his case. Once a translator was secured, the patient was able to tell staff he had a diabetic condition and get his basic needs met, including access to a shower as indicated by the bathtub. Also, due to his undocumented status, the police were called and stood guard outside the patient's room; this was represented by the two green soldier figures. The student was tearful during the debrief of this tray, stating, "My heart was breaking for him, and it felt like this was all too real since I have family members that only speak Spanish. This story will stay with me as a reminder of the importance of empathy and compassion; every hospital has a language line that we can use in these instances to help us understand our patients."

Advanced: Trauma Informed Care Principles. Lastly, the workshop ended by explaining how no one can "pour from an empty cup;" however, once the students become practiced at refilling their own "cup," they can begin to pay that abundance forward. We discussed with participants how regular practice of mindfulness and self-compassion techniques will provide them with a wide and robust window of tolerance. This may allow them to show up better for the people they serve; they will become adept at remaining centered as situations attempt to disrupt their emotional state. Additionally, this intimate knowledge of the window of tolerance can help them have greater compassion and understanding for the behaviors of their patients; knowing each person has their own window of tolerance and, as a patient, is experiencing a highly disruptive event that is leading them to express a hyper- or hypo-aroused state, fosters empathy. We then explained this place of empathy and compassion for patients provides the equipment necessary to practice trauma-informed care.

The participants learned trauma-informed care has five principles: safety (ensuring physical and emotional safety, respecting privacy), choice (the individual has some choice and control in their care), collaboration (we make decisions with the individual, share power), trustworthiness (we are clear with tasks, consistent, and set interpersonal boundaries), and empowerment (we provide validation and affirmation to the individual) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Results

To our knowledge, utilizing sandtray as a component of a mindful self-compassion intervention is a novel approach. Additionally, the vulnerability required for fostering moments of shared humanity can make some people uncomfortable. As such, we were not sure how the participants in the workshop would feel about the sandtray component applied for this purpose. We gathered post-intervention feedback via a multiple-question survey; the two questions most applicable to assessing the participant perceptions regarding the sandtray component were: (1) Describe your thoughts on the sandtray component of this training. How did it impact you? and (2) What is the most impactful practice, thought, or experience you are taking away from this training?

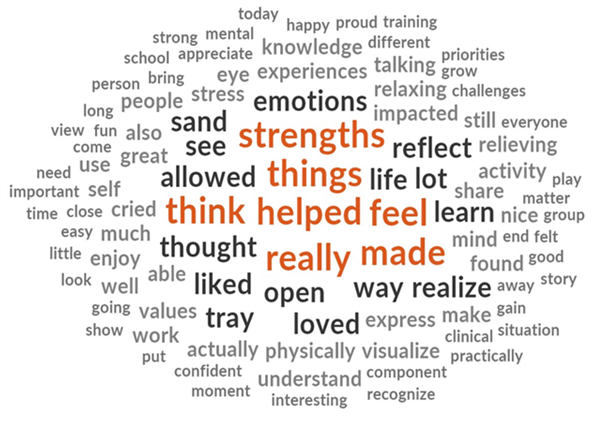

Figure 5: Participant Responses - Describe Your Thoughts on the Sandtray Component of this Training. How Did it Impact You?

Participant Thoughts on the Sandtray Component

Figure 5 is a word cloud analysis of the participant responses to the first question, which asked them to share their thoughts on the sandtray component of the workshop, and how it impacted them. The size and color of each word indicate the frequency with which it was used.

>We can see in bold, black font the words "liked" and "loved," along with the words "sand" and "tray." Regarding impact, we see large, bold, and in red font, the word "helped," with surrounding words like "allowed," "reflect," "open," "think," "learn," "see," and "realize," followed by "life," "strengths," and "emotions." Participants overwhelmingly enjoyed the sandtray component, feeling it helped them process emotions, realize strengths, and express themselves.

Participant Most Impactful Experience, Practice, or Thought

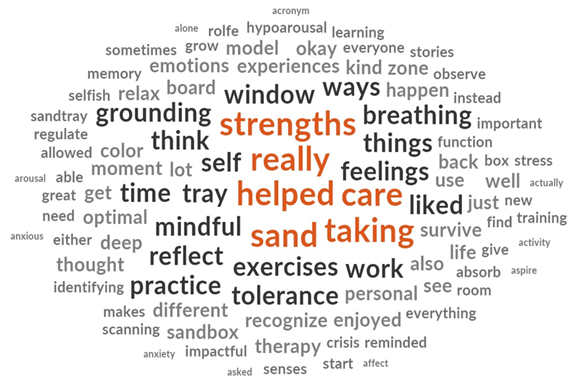

Figure 6 is another word cloud of the participant's responses to the second question, which asked participants to indicate what they believed to be the most impactful component of the workshop. This analysis indicates the sandtray component was most frequently cited as most impactful.

This is evidenced by the frequent appearance of the words "sand," "tray," and "helped." The word "strengths," appearing very frequently, as evidenced by its large, bold, red font, suggests the Strength Reflection and Affirmation Tray was a particularly effective tool for helping participants recognize and appreciate their personal abilities and resilience. Additionally, the words "mindful" and "exercises," along with "breathing" and "grounding," indicate the participants found this aspect of the workshop to also be impactful. This is evidenced by the words mindful self-compassion practices, helpful for managing those emotions.

Figure 6: Participant Responses - What is the Most Impactful Practice, Thought, or Experience You are Taking Away from this Training?

Discussion

We incorporated a series of sandtray builds into mindful self-compassion training for undergraduate student nurses to decrease burnout and increase understanding of mindfulness and self-compassion principles. An essential component of mindful self-compassion is shared human connection and experience; we believed sandtray would be an effective and well-received method for addressing this element. Approximately 80 students, in cohorts of 10, received the "window," "tolerance," "feelings," "self," and "care," it is clear participants found the window of tolerance a useful framework for understanding emotions and the use of self-care in the form of training, and 69 joined the study, providing pre- and post-intervention feedback via a series of surveys. Participants were asked to provide their perceptions of the sandtray component and what they found to be the most impactful aspect of the workshop. Thematic analysis using word clouds indicated participants overwhelmingly enjoyed the sandtray component, finding it helpful to reflect on strengths, life, emotions, and experiences and express themselves. Additionally, the sandtray component was indicated by participants to be the most impactful practice offered in the workshop.

The United States is facing a severe shortage of healthcare workers, especially nurses, which reduces healthcare availability and threatens the nation's health (Haddad et al., 2023). Burnout, characterized by exhaustion, cynicism, emotional distancing from one's work, and feelings of low professional efficacy (Maslach, 1993), is often cited as the primary reason nurses leave the profession (Shah et al., 2021). Mindfulness and self-compassion interventions have been demonstrated to lead to greater emotional strength and resilience among participants, which could reduce feelings of burnout and, subsequently, keep more nurses in the field (Salvado et al., 2021). Marrying sandtray with mindful self-compassion practices may offer a path for engaging nurses and other health professionals in deep and meaningful ways as a component of a greater mindfulness and self-compassion curriculum. In this capacity, sandtray and sandtray therapists could have a role to play in reducing the burnout epidemic in healthcare workers.

This work is one aspect of a more extensive, pre-post study evaluating the impact of this novel workshop on markers of burnout, as measured by the Maslach Burnout Inventory pre- and two-months post-intervention, which will be submitted for consideration by an academic journal in the coming months. Preliminary analysis indicates the intervention was effective at reducing burnout in this population.

References

Balban, M. Y., Neri, E., Kogon, M. M., Weed, L., Nouriani, B., Jo, B., Holl, G., Zeitzer, J. M., Spiegel, D., & Huberman, A. D. (2023). Brief structured respiration practices enhance mood and reduce physiological arousal. Cell reports. Medicine, 4(1), 100895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100895

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, Sep 17). Infographic: 6 Guiding principles to a trauma-informed approach. Office of Readiness and Response. https://www.cdc.gov/orr/infographics/6_principles_trauma_info.html

Dall'Ora, C., Ball, J., Reinius, M., & Griffiths, P. (2020). Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Human resources for health, 18(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00469-9

Eriksson, T., Germundsjö, L., Åström, E., & Rönnlund, M. (2018). Mindful self-compassion training reduces stress and burnout symptoms among practicing psychologists: A randomized controlled trial of a brief web-based intervention. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2340. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02340

Haddad, L. M., Annamaraju, P., & Toney-Butler, T. J. (2023). Nursing Shortage. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493175/

Kriakous, S. A., Elliott, K. A., Lamers, C., & Owen, R. (2021). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the psychological functioning of healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 12(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01500-9

Maslach, C. (1993). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research (pp. 19-32). Taylor & Francis.

Miller, K. I., Stiff, J. B., & Hartman Ellis, B. (1988) Communication and empathy as precursors to burnout among human service workers, Communication Monographs, 55(3), 250-265. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758809376171

Neff, K.D. (n.d.). Definition of self-compassion. Self-Compassion. https://self-compassion.org/the-three-elements-of-self-compassion-2/"

Neff K. D. (2023). Self-Compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual review of psychology, 74, 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047

Neff, K.D. (2019). The yin and yang of self-compassion: Cultivating kindness and strength in the face of difficulty. Sounds True.

Neff, K.D., & Germer, C.K. (n.d.). Center for Mindful Self-Compassion: The program. Self-Compassion. https://self-compassion.org/the-program/

Rolfe, G., Jasper, M., & Freshwater, D. (2010). Critical reflection in practice: Generating knowledge for care. Macmillan Education UK.

Salvado, M., Marques, D. L., Pires, I. M., & Silva, N. M. (2021). Mindfulness-Based Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Primary Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(10), 1342. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101342

Scheepers, R. A., Emke, H., Epstein, R. M., & Lombarts, K. M. J. M. H. (2020). The impact of mindfulness-based interventions on doctors' wellbeing and performance: A systematic review. Medical education, 54(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14020

Shah, M. K., Gandrakota, N., Cimiotti, J. P., Ghose, N., Moore, M., & Ali, M. K. (2021). Prevalence of and Factors Associated With Nurse Burnout in the US. JAMA network open, 4(2), e2036469. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36469

Siegel, D.J. (1999). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Publications.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Any further distributions of this work (noncommercial only) must maintain attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, journal citation, and DOI.

© World Association of Sand Therapy Professionals, World Journal for Sand Therapy Practice, Volume 1, Number 12, 2023