Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy in the Sand

Lisa Remey

Bluebonnet Center for Play Therapy

New Braunfels, TX, USA

There are no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lisa Remey, Bluebonnet Center for Play Therapy, 468 S. Seguin Ave. #203, New Braunfels TX 78130, United States.

Email: bluebonnetplaytherapy@lisaremey.com

https://doi.org/10.58997/wjstp.v2i1.72

Abstract

This article describes the application of sand therapy to Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT). An overview of CBPT is provided to consider how foundational theoretical aspects are applied to sand therapy. Case examples give the reader insight into how CBPT sand therapy may be used within a play therapy session. Case examples include both directive and non-directive prompts to demonstrate using either or both at appropriate times within a session. These are chosen through collaboration between client and therapist and are tied to treatment goals. Aspects of CBPT, including role play, CBT-focused facilitative responses, and psychoeducation, are also incorporated into the sandtray process.

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral play therapy, cognitive-behavioral sand therapy

Aaron Beck originated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) in the 1960s with theoretical roots in both cognitive and behavioral therapy approaches. CBT aims to identify clients' challenging and unhelpful thoughts and learn alternative thinking patterns and behaviors to improve feelings and meet client goals (Beck et al., 1979). The cognitive-behavioral model provides a lens through which therapists understand people's problems and conceptualize how they change. Judith Beck (2021) shares in CBT early writings the importance of foundational counseling skills of building trust and rapport, with the therapist demonstrating warmth, empathy, and genuineness as essential, and the therapeutic relationship as necessary to collaboratively work toward client goals (Beck, 2021). CBT sessions ebb and flow, with therapist and client collaborating to meet the client's individual needs. Session focus is flexible, allowing for shifts to explore client experiences, values, and beliefs to identify the effects on the client's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Aftab, 2021; Okamoto et al., 2019). Various techniques are utilized to support clients in addressing maladaptive beliefs and cognitions to promote increased adaptive beliefs and behaviors, which, in turn, shift cognitions to relieve distress (Beck, 2021). CBT is a researched theory that has proven effective and adaptable for adults, couples, families, children, and youth from diverse socioeconomic, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds, with a wide range of disorders, and with clients worldwide (Corey, 2022; Hofmann et al., 2012; Kazantzis et al., 2018).

Play is acknowledged as a child's natural approach to learning, exploring, gaining mastery, and developing an understanding of their world (ahmetoğlu & İlhan Ildiz, 2018; Brown & Vaughan, 2009). Play, as the language of children, with multifactored benefits in which roles are practiced, experiences are processed, emotions are expressed, and increased understanding of their world (Fuggle et al., 2013; Koukourikos, 2021; Landreth, 2024; Schaefer & Drewes, 2014). The roots of play therapy began with this understanding of play and how children process and learn about the world around them. Susan Knell (1995) identifies play as an invaluable tool for counseling children. Knell developed Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy (CBPT) for use with preschool-age and older children, tailoring CBT to meet their developmental needs specifically. Friedberg (2018) explains that using storytelling, play, and games is beneficial to increasing engagement in sessions, as well as psychoeducation teaching skills and adaptive coping mechanisms. Concrete play provides an opportunity to understand concepts and express thoughts related to presenting problems without relying on open-ended questions (Cavett, 2015). CBPT utilizes verbal and nonverbal activities within this developmental framework. CBPT is based on behavioral concepts and social learning to change negative behaviors with structured and unstructured play within sessions (Knell, 2022, 2015, 1995). Facilitative responses bring focus during sessions on the client's thoughts, perceptions, feelings, actions, and environment (Kottman, 2018; Ray, 2021). Similar to other play therapy approaches, CBPT therapists also utilize facilitative responses to teach skills, bring awareness to cognitions, develop adaptive thoughts, and provide options for alternative behaviors to increase positive functioning across various environments. Schaefer and Drewes (2014) identified 20 therapeutic powers of play, describing how play is the change agent in play therapy sessions. Through the powers of play, children enhance social relationships, cultivate emotional wellness, facilitate communication, and increase personal strengths. These factors are elements of CBPT sessions in which children, through play, shift cognitions, gain mastery over problems, and build self-efficacy. The therapeutic factors of play are evident throughout CBPT sessions. However, specific factors such as direct and indirect teaching, stress inoculation, and creative problem-solving occur frequently during a play therapy session's psychoeducational and structured portions. During the non-directive portions of a CBPT session, self-expression and abreaction are common therapeutic factors observed (Cavett, 2015; Drewes & Cavett, 2019; Knell, 2011).

CBPT aligns with the foundational play therapy belief of listening with both eyes and ears to build an understanding of what the child is communicating with their words and through their play (Knell, 2011; Landreth, 2024). Knell (2022, 2015, 2004, 1995) identifies aspects of CBPT, including a positive therapeutic relationship, modeling collaboration between client and therapist to move towards treatment goals, positive reinforcement, and role play to increase awareness of thoughts, feelings, and actions.

CBPT Application to Sandtray

Sandtray therapy is a cross-theoretical modality that supports using varied interventions and approaches (Holliman & Foster, 2023; Homeyer & Lyles, 2022). Sandtray therapy can be directive or non-directive, utilize various approaches and techniques, and be verbal or nonverbal (Homeyer & Sweeney, 2023; Sweeney, 2021). Within the CBPT framework, sand tray interventions can also be collaborative, client-led, therapist-led, directive, or non-directive. CBPT prompts are based on the client's treatment goals to build awareness of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors within the sand tray.

When considering integrating a sand tray into sessions, it is essential to understand developmental aspects between the relationship of images and language, storytelling, and how it relates to the application of a sand tray. Developmental theorist Damasico (1999) states that individuals think first in images before developing the ability to share stories through language. These images, created during moments experienced, become the first form of nonverbal storytelling. This understanding of thinking first in images leads to an increased understanding of how a person may think in images rather than through the use of language. Judith Beck and Norman Cotterell (Beck Institute video & personal communication, 2020; Beck, 2021) also relate how automatic thoughts can be in a picture format or a visual image before the individual is able to express thoughts verbally. These images can then reveal and reinforce automatic and adaptive beliefs. Therefore, CBT techniques using imagery can heighten positive emotions, practice coping techniques, and shift cognitions (Beck, 2021).

Storytelling and development are considered to be primary ways in which the brain integrates itself (Kestly, 2014; Siegel & Bryson, 2011; Siegel & Hartzell, 2013). Siegel and Hartzell (2013) consider how a person's perceived reality consists of the construction of life stories, and as a way, the brain integrates itself specifically through images. Storytelling naturally occurs nonverbally and precedes language development (Damasio, 1999). This understanding of images, storytelling, and development is bridged by Kestly (2014), bringing storytelling to sandtray therapy. Kestly illustrates this by stating that clients benefit from the nonverbal, playful sharing of stories and unresolved experiences in the sand tray while witnessed by a caring and attuned therapist, which develops a deeper understanding of these concerns. This increased understanding not only integrates the brain shifting from what may have previously been disjointed and chaotic but also builds mastery and resilience (Kestly, 2015). Badenoch (2011) also describes the development of storytelling as an internal process occurring unconsciously and without language derived from the attempt to create meaning in experiences, resolve conflicts, and plan.

Sandtray therapy provides an opportunity for the development of therapeutic metaphors. Metaphors created within the sand tray can offer both a sensory and regulating experience while simultaneously providing a safe distance to explore difficult issues (Homeyer & Sweeney, 2023). This aligns with the use of images and metaphors within the framework of CBT. Metaphors are a way of understanding experiences and the world around us, inner life thoughts and feelings, such as understanding change, similar to the ebb and flow of ocean waves. Killick et al. (2016) describe how metaphors are embedded in our language and help explain concepts effectively by providing visual images. Killick and colleagues expand on how children naturally enjoy symbolism, storytelling, and make-believe play, which can serve as a lens of how the world is viewed and how they process their experiences.

Integrating Sand Tray within CBPT Sessions

There are many reasons to introduce and utilize sand tray, storytelling, and prompts within CBPT sessions. These range from assessment, psychoeducation, modeling, skill building, client exploration, and even termination. Specifically, a client may appear to be progressing toward their treatment goals, and the therapist may introduce the sand tray and provide a prompt to assess that progress. Introducing the sand tray as a change of intervention within a session offers an opportunity to explore a feeling or experience in a new way. With the known benefits of storytelling and sandtray therapy reaching the conscious and the unconscious, new aspects of situations can be viewed and CBPT strategies applied (Friedberg & McClure, 2018; Knell, 2022; Schaefer & Cangelosi, 2016; Sweeney & Homeyer, 2009). The therapist's introduction of the sand tray may support the client's growth and appear differently depending on the phase of the counseling process. For example, suppose the therapist decides to introduce the sand tray during the initial phases of counseling. The goal may be to assess or identify feelings, experiences, and thoughts regarding current situations. Introducing the sand tray during the working phase allows the goals to shift the sessions by introducing new play options or directives to assess progress, practice skills, and role-play coping strategies. Once the sand tray is introduced, a client may request to utilize the sand tray in future sessions. Case examples will demonstrate how sandtray prompts are used at different phases of treatment and specifically tailored for each client's needs.

CBPT Sand Tray Prompts

The benefits of sandtray therapy include increasing self-awareness and providing relational safety when creating within the sand tray, reaching both the conscious and unconscious (Homeyer & Sweeney, 2023). When considering sandtray from a CBPT perspective, the sand tray is used to explore links between client thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and can be therapist or client-led. Sometimes, clients may choose the sand to create their own story or world. In this case, the therapist may follow the client's lead, focusing on facilitative responses that contribute to working towards identified treatment goals. At other times, the therapist may give a specific prompt. Prompts can be varied from an open-ended invitation to a specific directive. A few examples of open-ended prompts are "build a world of feelings," "create a world," or "share a story in the sand." More directive prompts focus on specific topics, skills, and/or feelings, such as "show a regular day at school," "show a world of calm and mad," or "tell a story about a family." Role-playing and modeling are other interventions a CBPT therapist may utilize within the sand tray. Modeling and role-playing are often through bibliotherapy, puppet storytelling, or character role-playing. However, these approaches can be easily adapted to the sand tray. As mentioned, storytelling and images are a natural part of language development and, for some, an automatic response to reflecting on experiences and/or feelings. Using images within the sand provides an alternative means to practice learned skills, identify new skills, explore relationships, and build self-awareness (Homeyer & Sweeney, 2023). Through specific prompts and CBPT facilitative responses, using the sand tray provides an opportunity to apply skills and strategies concretely while exploring within the safety of the play therapy session and within the safety of the sand tray.

CBPT Processing of Trays

Facilitative responses in play therapy sessions are verbal responses by the therapist that build the therapeutic relationship, reflect verbal and nonverbal occurrences, reflect content and feelings, and build client self-awareness (Landreth, 2024; Ray, 2011). These therapist reflections build empathy and understanding and communicate caring acceptance without interrupting the natural flow of play (Landreth, 2024). Within the CBPT framework, theory can be observed through specific prompts and facilitative responses when processing a client tray. CBPT facilitative responses increase understanding of thoughts, feelings, and actions. From a CBPT perspective, the therapist assesses and gains an increased understanding of the client's inner world and perspectives. CBPT facilitative responses reinforce learned coping strategies and build on skills.

One difference between CBPT and other theoretical frameworks of facilitative responses is integrating psycho-educational content, skills, strategies, and therapist prompts to guide sessions. This, however, does not mean the CBPT therapist ignores the client's response and shifts to a structured therapist-led session. On the contrary, a CBPT therapist remains client-focused, listening with eyes and ears to client responses when prompts and inquiries are made to identify client viewpoints, thoughts, and feelings and collaboratively continue session play and activities and, as in other theoretical approaches, remains sensitive and aware of client reactions (Cavett, 2022; Knell, 2004).

Case Examples

Case Example #1: Jeffery; Spontaneously Exploring the Sand

Sometimes, a client selects the sand tray for self-initiated, non-directive play. This case example is with Jeffery, age 8. This case identifies how CBPT facilitative responses are utilized when the client is not prompted to create a world or scene but spontaneously engages with the sand tray and materials.

Jeffery's treatment goals are based on school difficulty in attending to academic work and increased "meltdowns" at home. Play therapy sessions focus on building an increased understanding and acceptance of a range of emotions, identifying and utilizing coping strategies to decrease emotional outbursts, and improving his ability to complete academic tasks. CBPT play therapist-led portions of the sessions consist of gameplay, bibliotherapy, and interventions to explore emotions and learn and apply coping strategies and adaptive self-talk. The sand tray was introduced, with Jeffery choosing to manipulate and explore the sand rather than placing miniatures in the tray. During his self-directed sand tray play, I focused on utilizing facilitative responses to bring awareness of thoughts, feelings, and actions. Jeffery requests the sand tray in future sessions, chooses tactile play, and expresses feeling calm and relaxed when playing in the sand tray.

Here is a sample of how facilitative responses were utilized to reinforce concepts explored in sessions with italics as counselor statements (parenthesis representing non-verbal expressions), and [brackets reflecting the therapeutic approach].

Play therapist: Your body slowed when you started moving the sand around. (pause and observe) You are moving the sand all around. (pause, observe) You can squeeze it, hold it, let it go. (pause, observe) There are many choices that can be made [reinforcing ability to choose and plan own actions]

Play therapist: I can also see you're calm. I notice your relaxed shoulders, your body moving slowly and smoothly, and your face as relaxed. (pause) What do you notice about your body?

Jeffery: I feel relaxed overall and feel calm. (looks and smiles at play therapist) I wish I could have a sand tray at home to use in my room when I go to calm down.

Play therapist: [reinforce the desire to utilize strategies] Sounds like you want to find the same sense of calm at home, and when upset, I wonder what other ideas we can come up with that you could use at home?

Jeffery: I could use fidgets, listen to music, or read.

Play therapist: [build strategies] Those sound like helpful ideas. I wonder if playing with playdough would have a similar calming effect like the sand?

Jeffery: (continues to manipulate sand, experimenting with holding and releasing, piling, and burying hands and arms)

Play therapist: [tracking actions] You can hold the sand, let it go slowly, pile it together, and even bury your hands and arms in the sand. I imagine each feels a little different.

Jeffery: You try it.

Play therapist: (joining sand tray play mirroring Jeffery's actions) [tracking actions and building awareness of body and sensations experienced] The sand feels different depending on what we do. Sometimes, the sand seems hard, then soft when I relax my hand, heavy on my arms yet light and soft when sprinkled. I notice my body is also calm, my brain is relaxed, and I even have calm, slow breathing.

This case illustrates integrating facilitative responses when a client chooses non-directed play in the sand tray, providing examples of bridging skills identified in previous sessions and meeting the client where they are to collaborate towards achieving treatment goals.

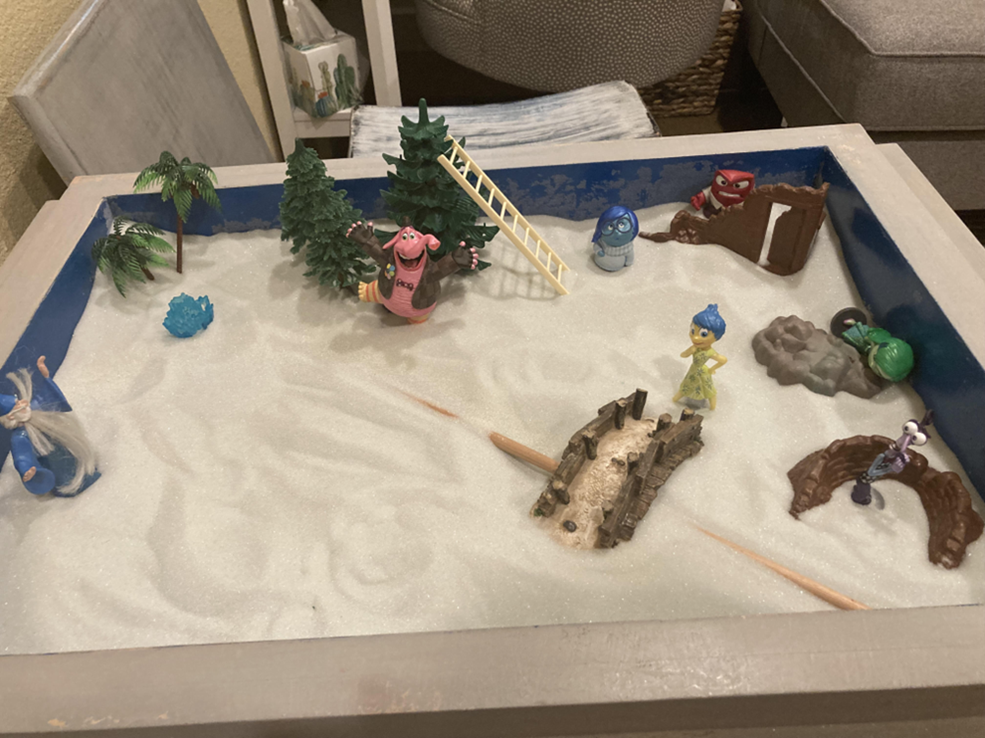

Case Example #2: Sarah; Therapist-Given Open Prompt Integrating Understanding of Feelings

Sarah is a 9-year-old female with treatment goals focusing on coping with anger, learning skills to cope with easily hurt feelings when communicating with peers, and difficulty processing experiences and feelings relating to peer and family relationships. During sessions, Sarah and I both selected activities. Interventions included art, music, gameplay, bibliotherapy, role-playing, and story prompts. The sand tray was introduced in session six, with Sarah initially exploring the sand. I then provided the prompt to "create a world." Initially, Sarah appeared hesitant and unclear on how to approach the task and began looking at the Inside Out© miniature figures (Docter & Del Carmen, 2015). Inside Out© characters were used in previous sessions to explore feelings and in storytelling. As she appeared unsure how to begin, I expanded the original prompt with "One idea could be creating a world using the Inside Out© figures." This prompt appeared to help as she then began to build her world. An area for each Inside Out© character was created (Figure 1). As building the tray, a large portion of time was spent on the area where Sadness was placed, changing, and adjusting items. After the tray was completed, I began processing her scene by asking about the different areas.

Play therapist: [opening question to begin processing of tray] Tell me about what you created.

Sarah: (pointing to areas) Each feeling has their own area and a pet to keep them company.

Sarah: Joy's area is in the woods with a path, so others are welcome and can join her. She has a peacock as a pet. She sees the good in things around her.

Play therapist: (active listening as Sarah describes tray with non-verbal interactions)

Sarah: Scared's area is fenced in and helps him feel safe and less scared. He has a donkey as a pet because they are calm and protective. Disgust stays at the beach, hangs out with alligator and doesn't like anything. Anger is fenced in with fire, and he is just mad. He likes to be alone when mad and yell. He has a pet lion who is also mad and roars loudly. Sadness is in a box (miniature jail) all alone. There is another sad person in the corner because Sadness's sadness makes others around her sad, too.

Play therapist: [increase understanding] I notice some areas are open and others are closed

Sarah: Sadness has an opening in the fence so she can join other areas if she wants. Disgust has a small space to come and go from, and Fear has a place to hide. (she then created an opening within Fear's area) I want him to be able to leave and not be stuck there. Mad is fenced in to protect him and others from his outbursts.

Sarah's tray demonstrated her understanding of the uniqueness of each feeling, giving insight into her perspective and challenges integrating multiple feelings. At the end of the session, a brief check-in was completed with the parent, who shared Sarah's significant changes at home, such as increased calmness, increased positive interaction with others, increased patience with siblings, and observed effort to utilize coping strategies.

Sarah continued attending sessions with a focus on building and integrating skills. Four sessions later, Sarah and her parent reported an increased ability to cope with emotions, reduced emotional reactions, and reduced peer conflicts. During check-in, Sarah requested to create another sandtray.

Play therapist: [assessment prompt given providing a wooden dowl for a split tray, the goal of identifying client coping skills] How about a tray showing how big emotions move to calm?

Sarah: (nodded and explored miniatures, placing the wooden dowl in the tray diagonally and selecting the Inside Out© miniatures and describing as creating the tray) (Figure 2) Joy is in the forest exploring happily, always seeing the positive and happy all the time. (A ladder was then leaned up against a tree) The ladder is there to remind joy that sometimes you might be sad and that it is ok to have changing feelings, like going up and down a ladder. It can even be helpful to cry sometimes. (Sadness is then placed near the ladder) Mad's desire to be alone just to be mad and break everything, yet can come out when madness is smaller. Disgust, not knowing what to do, and bored with thoughts like "Ugh, my friends won't get me," which results in doing whatever she wants and just staying disgusted. Afraid is scared of everything with no desire to do things due to ongoing fear.

Next, Sarah began reflecting on the two areas she had created with the dowl as a divider. Sarah added a bridge in the middle, overlapping the two areas to allow feelings to move to the calm portion of the tray. Sarah identified the calm side as consisting of a professor, a palm tree, and waves ("because waves are calming").

Play therapist: Tell me more about this side of the tray

Sarah: The calm side is an area in which you can be yourself, take a break, have fun without caring what people say, and no longer get mad or sad all the time. Joy is considering going over to the calm side, knowing that all feelings can come because all emotions are within her.

Play therapist: [CBPT prompt to assess self-talk coping strategies] What kind of things does she tell herself?

Sarah: (pointing to and responding as Joy) It's fine, it's ok, and I can handle different feelings

Sarah's sandtray provided an opportunity to explore how feelings can change concretely. My assessment of Sarah's sandtray, based on her description, as well as coping self-talk examples, demonstrated growth. She also demonstrated, when building open areas, acceptance in integrating feelings to accept a range of emotions, each within herself, including calm.

Sarah's tray, in some ways, reflects a possible internalized struggle regarding processing and internalizing feelings. The calm side created as "empty" may indicate her difficulty integrating commonly experienced emotions with calmness. This awareness can be noted and then considered in future sessions. Sarah, however, presented her tray with positive affect, demonstrating an understanding of coping self-talk as a helpful tool in shifting feelings experienced. Following Sarah's lead, my reflections, and responses within the CBPT framework focused on these aspects. Future sessions will focus on building a sense of self, continuing to build coping self-talk, and understanding and integrating feelings.

Case Example #3: Maria; Client’s Development of Metaphor

Maria is a 14-year-old female seeking therapy to cope with a negative view of self due to past choices that continue to impact her daily thoughts and activities. Sessions consist of Maria sharing her experiences, past decisions, changes made, and current struggles. CBPT sessions with Maria include utilizing bibliotherapy, art, role-play, gameplay, and music. She is consistently actively engaged in sessions with self-motivation for change. During session thirteen's check-in, Maria shared her frustration with overthinking and past choices continuing to pop into her thoughts, expressing a desire to move forward and let go of past mistakes. When I asked what she did when thoughts popped into her head, Maria said she avoided them and did not utilize the coping strategies identified in the sessions. She said that in the moment, she forgets all about applying skills learned. We processed previous sessions and discussed the benefits of trying approaches to shift maladaptive thoughts. Reflecting on Maria's frustration and feeling stuck, as well as knowing Maria relates to hands-on and visual interventions, I introduced the sand tray to see how a different approach might explore cognitive distortions, thoughts, and feelings.

After introducing the sand tray, I provided a prompt of "create a world," with Maria creating a tray with a fence on the right side of the tray, a butterfly, a bridge in the center, and a trophy on the left side of the tray (Figure 3). When I asked her to share about her tray, she explained that the butterfly was crossing the bridge towards the trophy. Maria then shared the metaphor of making changes, comparing her process as similar to how a butterfly changes. I reflected on the difficult metamorphosis of butterflies. One that takes time and has different stages along the journey, each as unique before emerging from its chrysalis. Together, we reflected on the steps she had already taken on her journey of transformation. I then asked her to share about the other parts of the tray. Maria shared that the fence represented a barrier between the butterfly and the past. She explained that the butterfly chose to continue their journey, crossing the bridge towards the trophy and not looking back at the past.

Maria decided to create a second tray telling a story with the theme of a baby bird defying rules. She shared how even though the baby bird broke the rules, it continued to have support from parents with the option to return to the nest and to try again. She shared gratitude for her parents, who support her and believe in her. Maria chose to create a third tray that integrated themes from the bird's and butterfly's journey. The introduction of the sand tray provided Maria with a new way to explore and create her own metaphor for change.

Case Example #4: Jamal; Directive Split Tray to Assess Client Progress

Jamal is a 7-year-old male with treatment goals of reducing anger outbursts at home, which result in damaged items. Parents report the client's anger escalating in response to parental requests and undesired statements. Play therapy sessions include gameplay, bibliotherapy, and non-directive play. The sand tray was introduced during the beginning phase of counseling, with the client utilizing it intermittently during subsequent sessions. Jamal primarily focused on manipulating the sand, stating enjoyment of the soothing and calming feel. During check-in on Jamal's sixth session, he shared experiencing reduced feelings of anger and the ability to notice when becoming angry and use coping strategies. During the session, Jamal requested the sand tray. After a brief time manipulating the sand, I gave a prompt to create a split tray representing a world of anger and a world of calm. As I quietly observed, Jamal appeared to thoughtfully select miniatures and place them in the two parts of the tray.

After the completion of that tray, an invitation was given, inviting Jamal to share his tray (Figure 4). He described the right side of the tray as mad and the left side as calm.

Play therapist: [open prompt to share] Tell me about the different sides of the tray.

Jamal: (pointing to the mad side of the tray) The mad side gets mad at everything around them and cannot control their anger. (pauses, then points to the other side of the tray) The calm side also gets mad but can control their anger.

Play therapist: [clarification prompt] I notice this figure (pointing to Hades) on the calm side.

Jamal: Hades is on the calm side because anger and problems are still there, but on this side, the characters can keep their anger from growing.

Play therapist: [prompt to assess understanding and integration of self-talk as coping strategy] I wonder what the different characters might be telling themselves.

Jamal: (pointing to the mad side) I don't know how to do this, I'm bad, and they are just being mad.

Play therapist: What about on the calm side?

Jamal: (pointing to the mad side and to individual characters) They tell themselves; I can handle it; it's okay to get mad, you don't have to get that mad, and I can fix this.

The sand tray was utilized near the end of treatment to assess progress and potential termination. Jamal's sandtray world demonstrated an increased understanding of thought processes, coping with anger, and applying coping self-talk. Termination session planned based on reaching treatment goals and alignment with his self-report and parent report of ability to cope with anger outside of sessions.

Conclusion

CBPT utilizes both directive and non-directive approaches in play therapy sessions. This can also apply to sand therapy prompts. The play therapist could introduce the sand tray, allowing the client to create a non-directive or directive tray. With either approach, the play therapist keeps the treatment goals in mind.

During the creation of the tray, facilitative responses focus on tracking, reflecting, and play therapist's observation of the items selected. CBPT theoretical approach can be observed during the post-creation and processing of the tray. During the processing, the play therapist ties relevant thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that correlate with client concerns and skills working within sessions.

References

Aftab, A. (2021, October 5). The past, present, and future of cognitive behavioral therapy: Q&A with Judith S. Beck, Ph.D. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/past-present-future-cognitive-behavioral-therapy

ahmetoğlu, E., & İlhan Ildiz, G. (2018). The Friedrich Froebel Approach. In E. Atasoy & I. Koleva (Eds.), Recent researches in education (pp. 355–366). essay, Cambridge Scholars Publisher.

Badenoch, B. (2011). Being a brain-savvy therapist workbook: a companion to being a brain-wise therapist. W.W. Norton.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression (1st ed.). Guilford Press.

Beck, J. S. (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy: basics and beyond (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Brown, S., & Vaughan, C. (Collaborator). (2009). Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. Avery/Penguin Group.

Cavett, A. M. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral play therapy. In D. A. Crenshaw & A. L. Stewart (Eds.), Play therapy: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice (pp. 83–98). The Guilford Press.

Corey, G. (2020). Theory And Practice Of Counseling And Psychotherapy, Enhanced. (10th ed.). Cengage Learning Custom P.

Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Harcourt College Publishers.

Docter, P., & Del Carmen, R. (2015). Inside Out. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Drewes, A. A. (2009). Blending play therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy: Evidence-based and other effective treatments and techniques. Wiley.

Drewes, A., & Cavett, A. (2019, September). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. Play Therapy, 14(3), 24-26.

Friedberg, R. D., & McClure, J. M. (2018). Clinical practice of cognitive therapy with children and adolescents: The nuts and bolts (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Fuggle, P., Dunsmuir, S., & Curry, V. (2013). CBT with children, young people & families. Sage.

Hofmann, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J. et al. (2012). The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research (36), 427–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1

Holliman, R., & Foster, R. D. (2023). The way we play in the sand: A meta-analytic investigation of sand therapy, its formats, and presenting problems, Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 9(2), 205-221.

Homeyer, L. E., & Sweeney, D. S. (2023). Sandtray therapy: A practical manual (4th ed.). Routledge.

Homeyer, L. E., & Lyles, M. N. (2022). Advanced sandtray therapy: Digging deeper into clinical practice. Routledge.

Kazantzis, N., Luong, H. K., Usatoff, A.S. et al. (2018). The Processes of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-Analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research (42), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-9920-y

Kestly, T. (2015). Sandtray and Storytelling in Play Therapy. In D. A. Crenshaw & A. L. Stewart (Eds.), Play therapy: A comprehensive guide to theory and practice (pp. 156–170). The Guilford Press.

Killick, S., Curry, V., & Myles, P. (2016). The mighty metaphor: A collection of therapists' favourite metaphors and analogies. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 9, E37. doi:10.1017/S1754470X16000210

Knell, S. M. (2022). Cognitive Behavioral Play Therapy. In: Friedberg, R.D., Rozmid, E.V. (eds) Creative CBT with Youth. Springer, Cham.

Knell, S. (2011). Cognitive-Behavioral Play Therapy. In C. E. Schaefer (Ed.), Foundations of play therapy (2nd ed., pp. 313–328). Wiley.

Knell, S. M. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral play therapy. O'Connor, K. J., Schaefer, C. E., & Braverman, L. D. Handbook of Play Therapy (2nd ed, pp. 119–133). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119140467.ch6

Knell, S. M. (1995). Cognitive behavioral play therapy. Aronson

Knell, S. M. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral play therapy. Rowman & Littlefield.

Knell, S. M., & Dasari, M. (2009). CBPT: Implementing and integrating CBPT into Clinical Practice. In A. A. Drewes (Ed.), Blending play therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy: evidence-based and other effective treatments and techniques (pp. 297–318). John Wiley & Sons.

Kottman, T., & Meany-Walen, K. K. (2018). Doing play therapy: from building the relationship to facilitating change. The Guilford Press.

Koukourikos, K., Tsaloglidou, A., Tzeha, L., Iliadis, C., Frantzana, A., Katsimbeli, A., & Kourkouta, L. (2021). An overview of play therapy. Mater Sociomed. 33(4), 293-297. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2021.33.293-297.

Landreth, G. L. (2024). Play therapy: The art of the relationship (4th ed.). Routledge.

Okamoto, A., Dattilio, F. M., Dobson, K. S., & Kazantzis, N. (2019). The therapeutic relationship in cognitive–behavioral therapy: Essential features and common challenges. Practice Innovations, 4(2), 112-123. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000088

Ray, D. C. (2021). Advanced play therapy essential conditions, knowledge, and Skills for Child Practice. Routledge.

Schaefer, C. E., & D. Cangelosi (2016). The World Technique. In Essential play therapy techniques: Time-tested approaches (pp. 179–182). Guilford Press.

Schaefer, C. E., & Drewes, A. A. (2014). The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change. Wiley Press.

Siegel, D. J., & Bryson, T. P. (2011). The whole-brain child: 12 revolutionary strategies to nurture your child's developing mind. Delacorte.

Siegel, D., & Hartzell, M. (2013). Parenting from inside out. TarcherPerigee.

Sweeney, D. S. (2021). Sandtray therapy. In H. G. Kaduson & C. E. Schaefer (Eds.), Play therapy with children: Modalities for change (pp. 9–24). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000217-002

Sweeney, D. S., & Homeyer, L. E. (2009). Sandtray Therapy. In A. A. Drewes (Ed.), Blending play therapy with cognitive behavioral therapy: evidence-based and other effective treatments and techniques (pp. 297–318). John Wiley & Sons.

Original content from this work may be used under the terms of the https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Any further distributions of this work (noncommercial only) must maintain attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, journal citation, and DOI.

© World Association of Sand Therapy Professionals, World Journal for Sand Therapy Practice, Volume 2, Number 1, 2024